Das Loch

There's a hole in the middle of the sea

A hallmark of Kafka’s writing is that there’s no good way to end a story about a system. The system, in a sense, is always self-preserving until the precise point it is made obsolete at once — if we could tell when that point is, then it wouldn’t decay into the hall of mirror horrors that he so beautifully (and terribly) describes in his work. With physical systems, we get the joy of technological progress — it’s increasingly clear to me every time I use Starlink that we have invalidated the need for telecommunication networks for personal use, that there’s no reason to build “out” when you can build “up” (and, of course, this kills the need to actually win the game of whack-a-mole with robocallers. The new buy-in to a new network renders the spoofing game obsolete.)

With abstract systems, however, the depreciation curve of a failing system is the decay of faith in the system itself,

What I realized is that the “trick” that kickstarts liquidity in a belief-based system (fiat) is the fact that you have to get people to believe in it. If I endlessly point out how everything is constructed around an assumption, and continuously harangue the point that “it’s not real”, it becomes a self-fulfilling reality if my ideas hit critical mass.

which is why life never gets better for Gregor Samsa after his metamorphosis. His life is one of tragic meaninglessness that exposes how a lack of intimacy in the human systems that hinge off it to function decay over time. So he dies, and such is life.

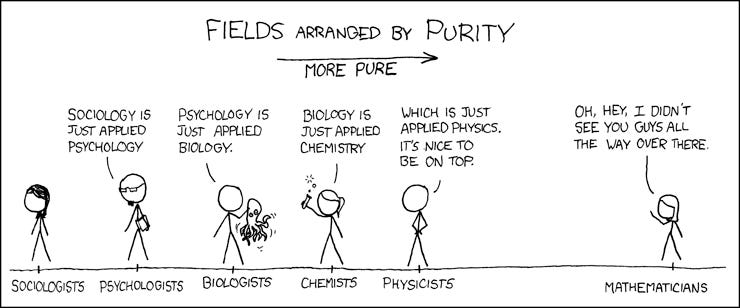

Abstract systems require a torturous dissonance to handle both sides of “theory” and “reality”, and the friction between it (aka, “liquidity”), which is why it’s easier to just pick one side or the other and feel superior about it. The applied side scoffs at the abstract side for never actually being able to process that a decision has to be made (aka, why libertarians simply never get that their policies can’t ever be properly scripted), and the abstract side snorts at the applied devotees for never understanding nuance. Spending too much time bouncing between sides turns you manic, or worse.

Innate to every abstract system lies a contradiction that, if debated enough, will eventually create enough dissonance so the system can remain resistant to capture. In law, this is the concept of “unauthorized practice of law”. For the unfamiliar, here’s the extensive definition, but I’ll clip out the key point:

The definition of the practice of law is established by law and varies from one jurisdiction to another. Whatever the definition, limiting the practice of law to members of the bar protects the public against rendition of legal services by unqualified persons. This Rule does not prohibit a lawyer from employing the services of paraprofessionals and delegating functions to them, so long as the lawyer supervises the delegated work and retains responsibility for their work

Is the recursion obvious here? I’ll spell it out another way:

The point of recursion where the system exists primarily to preserve itself is what I call the precise point where you can describe the system as “Kafkaesque”. My favorite example of this is the argument against the death penalty where, citing mandatory appeals processes, people claim that it’s “simply cheaper to house someone for life in prison” than give them the “mandatory” appeals that are part of “due process”.

This is stupid! Of course that’s not a logical claim! You’re using one part of the systemic definition to make a claim on its own properties. This contradiction is everywhere in law — disparate impact allows for an observation to be used as proof of discrimination,

such a devastating bit of circular reasoning that nobody bothers to correct because the inefficiency created is capturable by billable hours and settlement-seeking. The only thing that preserves this scheme is declaring that, if I notice the contradictions, this is unauthorized practice of law!

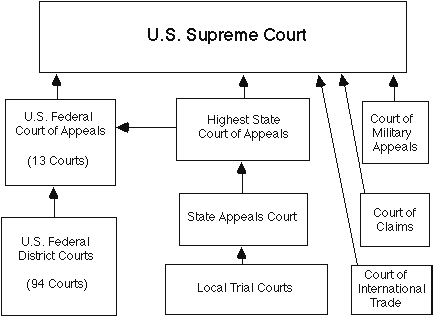

You might wonder how the legal system ever worked in the first place, and it’s a fair question. The concept of “jurisdiction” created a sufficiently segmented-but-whole graph that was, in theory, supposed to prevent abuse from crippling the system.

There is an endless amount of litigation over this concept, but it’s really quite simple — you have a directed graph where some cases can only flow one way, or be decided in a certain structure independent of the federal morass. (Put simply, you have a federal vs state split — what type of issue is this — and then “supreme” jurisdictions that can overrule lower nodes.

The appeals process is incredibly designed if you don’t allow, say, a bunch of district court judges to claim power over issues they don’t have.) This is a compressed chart, but the entire system bricks in two cases — when subject matter jurisdiction is incorrectly assumed by lower courts, or a jurisdiction becomes “hostile”.

The only way to put a rampant court system out of line, as I got tired of documenting in this thread, is to federalize it:

It is blatantly clear that multiple jurisdictions are unfixable. Really think about what the federalization of DC entails — it’s a test run as to whether deep blue jurisdictions that have long been out of control can be fully defenestrated.

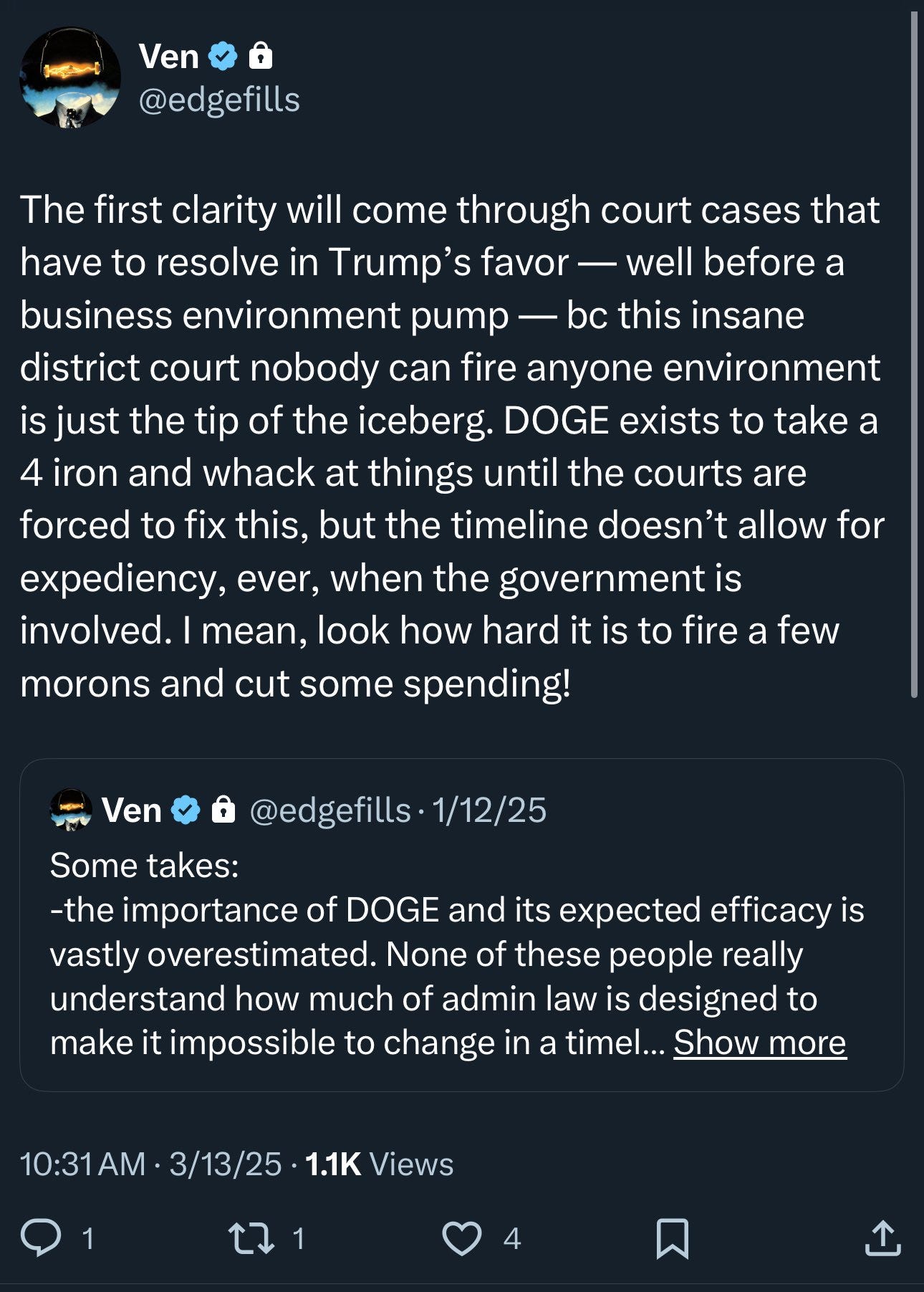

In a way, I think this is what made Elon so frustrated with DOGE, and why figuring out the American legal system drove me nuts (as I pointed out the Kafkaesque creations in the Onion Futures Act, the concept of insider trading, and the Howey definition of the security):

Admin law is one of the kookiest concepts to ever exist — where the logical understanding that, as the world gets more complex, a single President and cabinet could not possibly hope to make every decision through debate, so their executive power could be passed down into quasi-judicial and quasi-legislative bodies. In business, you have the shell corp, in law, you have the agency, which is always part of the executive, but, to prevent the situation where a single President is the direct center of the graph, there are odd exceptions in how he can directly control the executive power that has been granted to the agency. (In fact, this is entirely what I taught myself while following the Fannie Mae trade, and you can look to Trump v. Wilcox as to how the Federal Reserve board is tepidly insulated from “no cause” firings.)

I am positive that Elon saw the heart of the problem basically instantly, which is why he signed up to try and fix things. It was never about “cutting the budget”, it was entirely about bricking the court system in such a manner that, no matter what, the only way to preserve the system was to make the “chief executive” the ultimate node in the graph. I say this because it’s precisely what he did when he converted Twitter into X, and that is possible to do with the US legal system (if you dig into “unitary executive theory”), but when the solution is so obvious such that you just have to wait for it to play out, you go a little nuts sitting around and waiting for it to happen.

And, when Trump started to get this power handed by the Supreme Court who knows that the only way to remain relevant is to allow full federalization, and Elon didn’t get to share in it, it might have just been too much:

The second most painful breakup I’ve experienced this year was the one between Elon Musk and Donald Trump, partially because I got rinsed on what had the potential to be one of my biggest runners ever, but mostly because it means that there’s no time to rest and enjoy life as things will keep happening.

But, I think there’s another way to use tech to try and fix this system, rather than trying to become the central node in a system that cannot possibly allow it. And, now that everyone is consistently complaining about how there’s no organic content on the internet, there might be a cheeky little experiment to run with a bit of “legal AI”.

The problem I keep complaining about that is surely being noticed by everyone who consumes content on the internet nonstop is that AI-generated content sufficiently surpassed everyone creating content other than oddities and outrage farming. It’s why the only content seems to be “race war” that gets people organically posting again, whether it’s about the WNBA, “hate speech” go fund mes, Costco, or the worst bus trip video I’ll ever see in my life.

You see, there’s one exception to “unauthorized practice of law” — no matter what, “due process” does allow the individual to represent themselves (which is the root of my favorite SCOTUS case, Sloan v SEC, where an unpleasant oddball stumbled into a 9-0 victory, and thus got every non-lawyer banned from arguing in front of that court, which is a constitutionality discussion for another time), because how can you refuse to incriminate yourself (the 5th amendment) if you’re not even allowed to defend yourself in the first place?

This doesn’t mean that you should commit a crime and represent yourself, and indeed, most self-filings mostly fall in the realm of small claims court. But what AI can allow us to do is construct a paradox that renders the question of “unauthorized practice” moot. As it stands, lawyers, individuals, and judges are all using ChatGPT to hallucinate work anyway. The docket is full of autogenerated filings, with autogenerated commentary and decisions creating an ungodly cluster of god-knows-which circle of hell this is to sift through. But, what if you could use the allowance of pro se litigation to create a paradox that must be ruled on?

There’s the famous attributed Einstein quote about how insanity is doing the same thing over and over again while expecting different results. (I don’t really know how this makes sense, but it’s catchy.) But in the case of the legally deemed insane, we can use this definition to our advantage:

If you have a legally-declared insane person, someone who could not be deemed fit to stand trial, able to file a coherent legal claim themselves using an AI drafting tool, would this break the concept of unauthorized practice of law?

Either the tool is deemed illegitimate, which clearly cannot be the case given the level of attempted avoidance of doing the work themselves, or the pro se rights of the institutionally insane are violated, which, in a sense, would invalidate all of our rights to file claims, lest the Kafkaesque horror presented in The Trial become our reality, where a court can declare us insane without any say in the matter ourselves. If we remove unauthorized practice of law from consideration, a much more rapid reorganization of the court network would be possible, with all the credentials being reconsidered at once.

(Fun fact, you don’t actually need to be a barred attorney to sit on the Supreme Court so, in a sense, why should this be a hard requirement for any lower node? Lawyerly camaraderie died a long time ago, and the horror of entering this system is precisely that of what used to be a symbiotic system turning into a mandatorily adversarial one.)

Humans have a permanent advantage over AI in that we can conclude things intuitively

Quality sensitivity is a function of intuition, and downplaying this is denying the superpower of pattern recognition from minute amounts of data that the human brain possesses. There’s a famous story about Stephen Curry where, in the 2022 NBA finals, he noticed the rim was slightly too high during warmups because his shots weren’t going in. It’s just as true for someone like me who has probably read more in my 24 years of being literate than tens of millions of humans put together, maybe more. It’s so, so obvious when something is botted, astroturfed, poorly edited, copied and pasted, and inorganic that I’m shocked other people cannot see it..

and high frequency trading firms found this out the hard way during the Power Peg incident that took out KCG:

Knight Capital Group was an American global financial services firm engaging in market making, electronic execution, and institutional sales and trading. In 2012 Knight was the largest trader in U.S. equities with a market share of around 17 percent on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) as well as on the Nasdaq Stock Market. Knight’s Electronic Trading Group (ETG) managed an average daily trading volume of more than 3.3 billion trades, trading over $21 billion … daily.

It took 17 years of dedicated work to build Knight Capital Group into one of the leading trading houses on Wall Street. And it all nearly ended in less than one hour…

At Knight, some new trading software contained a flaw that became apparent only after the software was activated when the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) opened that day. The errant software sent Knight on a buying spree, snapping up 150 different stocks at a total cost of around $7 billion, all in the first hour of trading.

Under stock exchange rules, Knight would have been required to pay for those shares three days later. However, there was no way it could pay, since the trades were unintentional and had no source of funds behind them. The only alternatives were to try to have the trades canceled, or to sell the newly acquired shares the same day.

Knight tried to get the trades canceled. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) chairman Mary Schapiro refused to allow this for most of the stocks in question, and this seems to have been the right decision. Rules were established after the “flash crash” of May 2010 to govern when trades should be canceled. Knight’s buying binge did not drive up the price of the purchased stocks by more than 30 percent, the cancellation threshold, except for six stocks. Those transactions were reversed. In the other cases, the trades stood.

This was very bad news for Knight but was only fair to its trading partners, who sold their shares to Knight’s computers in good faith. Knight’s trades were not like those of the flash crash, when stocks of some of the world’s largest companies suddenly began trading for as little as a penny and no buyer could credibly claim the transaction price reflected the correct market value.

Once it was clear that the trades would stand, Knight had no choice but to sell off the stocks it had bought. Just as the morning’s buying rampage had driven up the price of those shares, a massive sale into the market would likely have forced down the price, possibly to a point so low that Knight would not have been able to cover the losses.

You don’t need to automate away the job of the lawyer, they signed up to check the validity of the sourcing and do all the paperwork we don’t want to do anyway. You want their job to be that of the trader who can hit the massive red “STOP TRADING” button, not generating endless amounts of scrawl on top of the mass already to be processed. And that does require rethinking what “practicing law” is — is it the actual gatekeeping of the court network that defines a lawyer, or allowing them a bit more weight in what cases can actually make it to the docket in the first place?

“Automating something away” is not just “replacing jobs”, it’s reducing the amount of friction in the system. Humans are pretty good at generating relationships that make life a lot easier than following an increasingly-complex set of mishmashing rules, maybe that’s how we fix law.