Unlock Me Immediately

A memoir, of sorts

You never forget the first future timeline you truly believed in — that freshman year crush that you’re positive it would have worked out with had the circumstances been different, that business idea that nobody else saw at the time that didn’t pan out with your involvement. For me, this is a story about a girl named Fannie Mae.

Junior year was an odd time in my life. I had just come off a stint in a Bay Area “algo trading” shop which amounted to the pocket change of VC’s being punted around on index futures based off of astrological signs (which didn’t work then, and used to be a running joke of mine for years, but nowadays, I bet I could make it profitable given what I see on TikTok.) I vaguely understood the idea of “superdays” and “summer internships” being an extended job interview, but the on-campus recruiting events where twerps in ill-fitting black suits hovered around IB associates like ants swarming a dropped ice cream cone repulsed me and I was sure there had to be a better way. In addition, I wasn’t really sure that I needed an internship — granted, I was punting around stocks and options like any other retail trader that came across WallStreetBets post-2020,

I started trading in 2014 after my inevitable scrolling through /biz/ and r/wallstreetbets piqued my curiosity just enough to try it out with my own money.

The first stock I ever bought was JBLU. I would check the price every single day, and I wondered why the share price would move in real time when everyone would trade around the news.

I learned just like everyone else did who got into trading during the 2021 retail mania market — I read WSB nonstop, hung out in the chatrooms, tried out the ideas I liked myself, and shared my own…

Back then, they weren’t called “memecoins”, they were called small cap biotechs. Stuff that would wildly swing around on the sentiment of retail punters on message boards, because that was the only place volatility existed in the market. I remember making (to me, back then) a fortune off of names like RLYP and AVXL, and dodging obvious garbage like BGMD. When I check in with my old WSB friends, some of them are still holding this crap, somehow.

but it was kinda working. Some napkin math convinced me that I’d be able to pay my rent, have some summer fun, and convince my freshman year crush to transfer back.

At a cursory glance, not all that much has changed in how I conduct my life other than the numbers got bigger, I’m on the move a lot more, and I actually know what I’m doing now.

By now I have it down to a science, but when you are 20 years old and have zero meaningful experience, you have to operate off reasonable assumptions as much as possible. I’d have charts running 17 hours a day as I picked the brains of people who swore by technical analysis, posters who claimed to do exhaustive due diligence on companies that I’d never heard of, and bored financiers in bars. The beauty of finance is that it truly rewards generalists — it rewards expanding your knowledge base “out” more than any other field, which does have the downside of creating the paradox where it’s the most interesting thing to think about, as there’s endless rabbit holes, but actually working in the field isn’t interesting at all, as the roles are so specialized.

The other downside is that you don’t actually build any useful skills. Trading profitably is this form of postmodern agnosticism where a nihilistic approach is the only way to properly manage risk which comes at the cost of having a grasp on what the value of “a dollar earned” actually is. True insight into what “money” is comes with an understanding of everything that you set your mind to learn and the lack of an ability to do anything tangible with the knowledge other than explain ad nauseam.

I start off on this note because I wish I knew what I was getting into back then:

[In true WSB fashion], I learned to trade options by gambling on phase 3 PDUFA trials. None of this was sophisticated, and in such a low volatility, low volume market, these strategies don’t work. Here are some selected amusing emails I sent to my brokerage account manager at the time (February 7, 2016), to get approved for more than covered calls and cash-secured puts

which would lead to my first big cashout on RLYP a couple months later (July 21, 2016):

Shares of Relypsa (RLYP) are spiking by 58.79% to $31.92 in early morning trading on Thursday, after Galenica agreed to buy the Redwood City, CA-based biotech for $1.53 billion.

My first hit was a lot more than free, it paid big. Undeterred, I looked for more big winners. I gravitated to biotech for two reasons: first, that it was the only volatility in those markets, and second, as I had worked in a lab for a couple of summers of high school, surely I understood the entire drug pharmaceutical pipeline. Ah, the naïveté (and arrogance) of youth…

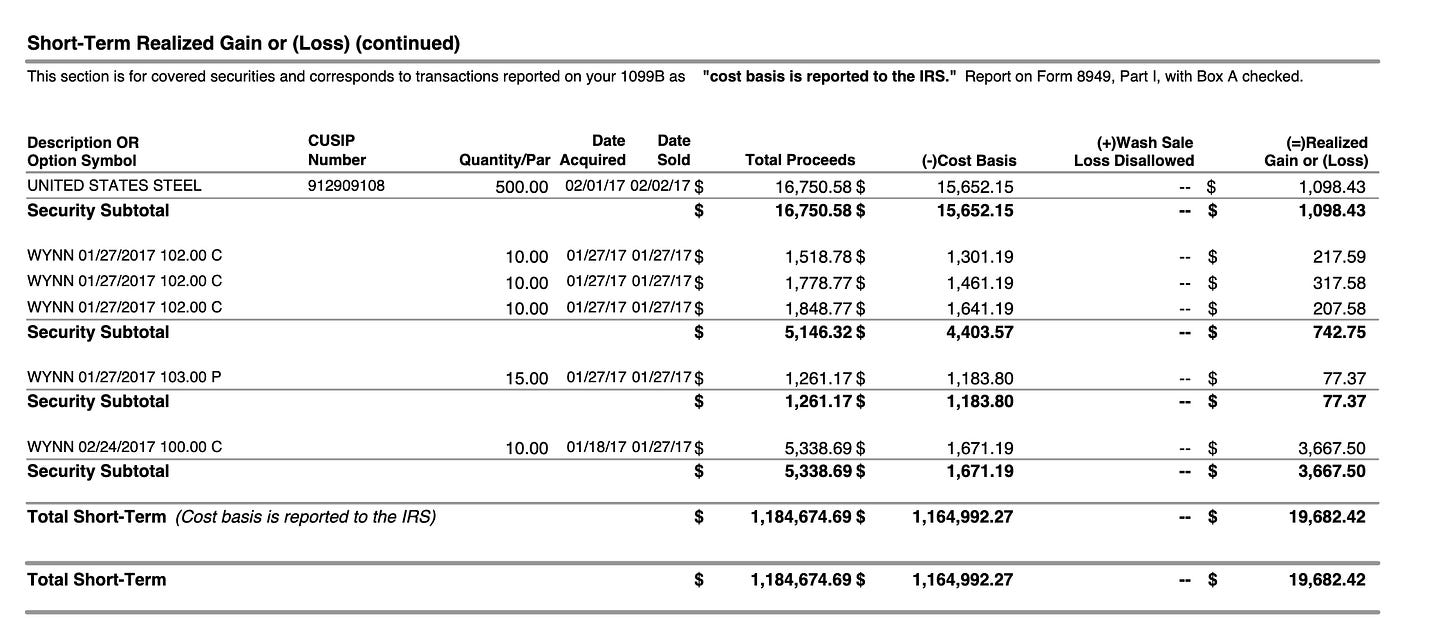

Revisiting my old statement from 2017, it was definitely pure luck that I made money. In many senses, I was the ultimate WSB creation — I made nearly 180 transactions to net just 20 grand in short term gains.

(Looking back, the fact that I didn’t lose money was pretty impressive, let alone the long term gains I had. On a % basis, I had a pretty damn good year.)

I hit every single retail ticker on the planet, and hit every weekly option to boot. When I scroll through this statement, I traded across AMD, AOBC, ARRY, XIV, JNUG, GSAT, LULU, NVDA, TSLA, index options, and more. The first idea that truly made sense, however, was when I came across a post on January 17, 2017.

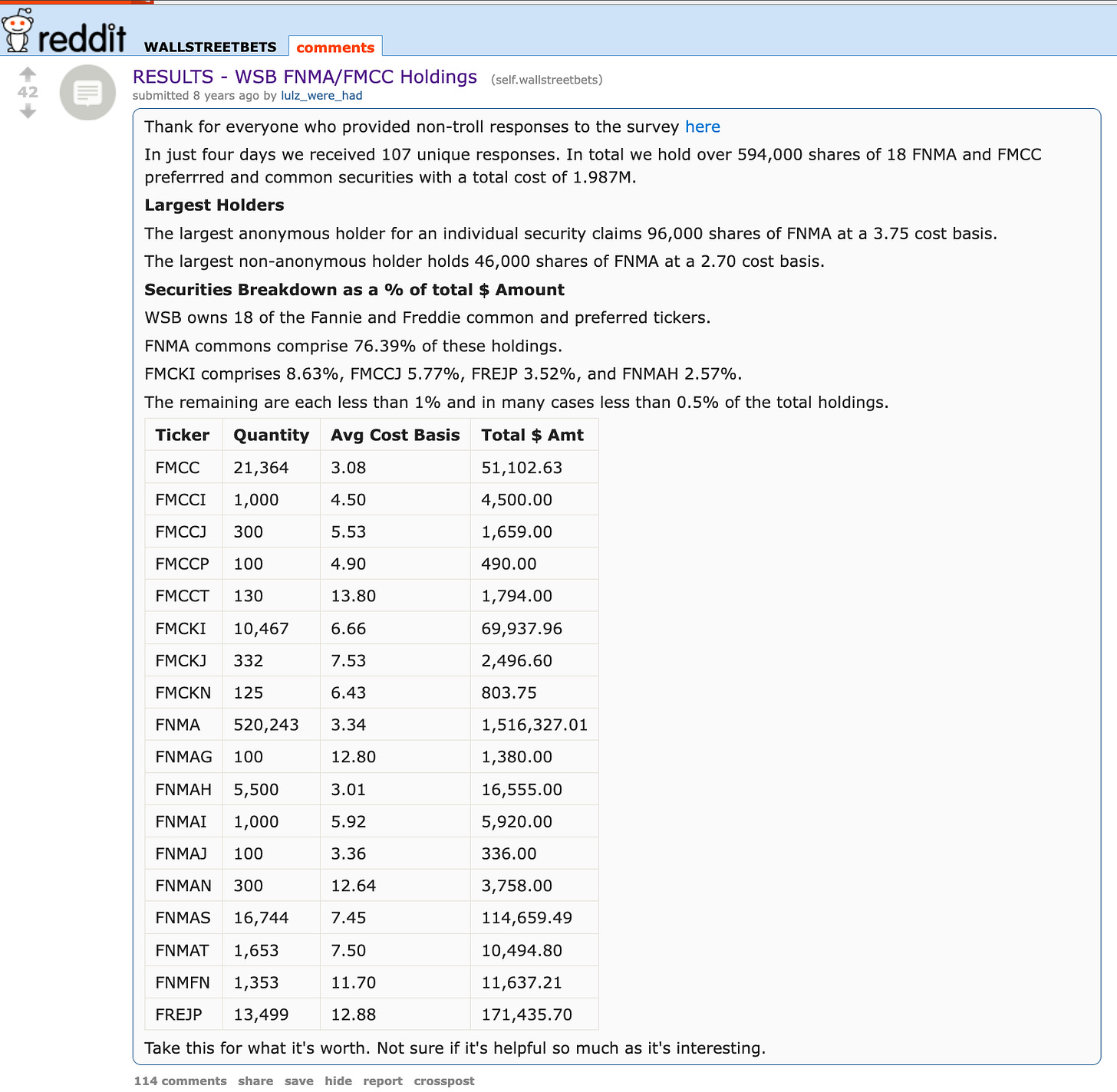

I had been casually reading about the Fannie conservatorship for a while — hedge funder gossip was very much what I was keeping up with, rather than the rest of my college’s Gossip Girl ennui — but seeing a subreddit of what was then ~100k users staking 2 million on a trade convinced me to take a swing myself.

And while I cashed out after making a quick 10% in a week, like any rational person would do, I still kept tabs on the story for years on end because I had never heard of “shareholder activism” prior:

(from Malt Liquidity 24, January 2021) A story I have followed with casual interest over the years is the fight to remove FNMA from government conservatorship, which was announced back in 2008. After the immediacy of the mortgage crisis was resolved, however, FNMA was never returned to private hands, and to this day remains a government-controlled entity. Since around 2010, shareholders realized that they were not getting any of the profits from the core business as the government was withholding the profits and neglected to inform the shareholders. This became an issue due to the fact that since FNMA had the government propping them up, they were the only mortgage lender actually providing mortgages in any real volume coming out of the recession, and they started making pretty large profits:

With interest rates low and banks not lending, Fannie and Freddie became the only mortgage game in town. By Sept. 30 of [2013], the companies had returned $185 billion to the Treasury.

But FNMA, like many stocks, has both regular shares and preferred shares which pay dividends. And a few hedge funds realized that if they bought the preferred shares, which theoretically entitled them to a portion of FNMA earnings but traded at a massive discount to the value they would be worth but for the withholding of earnings, and sued successfully, they might be able to alter the flow of FNMA profits from the Treasury to shareholders…

Two insights came to me immediately that, I think, still have deep implications today.

First, I couldn’t exactly understand what the common stock represented if not a right to some sort of future earnings. I had heard of the Merton Model at that point, but when there is a legal barricade, it’s far less quantifiable than approximating the recoverable value of an enterprise. Clearly, there were major flaws in the “fundamental assumption” given its intraday movements.

This implied a second realization: that markets depended on a certain type of information asymmetry related to a deterministic outcome. Similar to phase 3 trials, an explicit legal decision operated as an opening of the Schrödinger’s box to determine whether a trade idea was actually alive or dead. Indeed, the roots of postmodern market theory and my theory of insider trading derive from this brief moment.

I’m not exactly sure how I managed to sell the exact local top in this scenario, but the shares wouldn’t really take off until the end of Trump’s first term, and the dream died when other matters took priority in 2021, and Collins v. Yellen sealed the door shut during the Biden admin.

In any case, I proceeded to “solve” life from that point onwards by shelving theoretical concerns for the practical choice of having fun, which paid off in spades thanks to having the ability to shirk class with the equivalent of a solid analyst’s salary in disposable income to bounce around pre-inflation Manhattan with. (Then, consider the fact that Softbank was subsidizing every app on the planet, such that an Uber anywhere in lower Manhattan ran you less than a subway fare.) Through those extracurricular activities, I stumbled into a fortuitious friendship that landed me in a summer analyst role purely through coincidence, which I found out was a role that paid me about 85k pro rata to do absolutely nothing for 50 hours a week. Fortune favors those who don’t follow the crowd.

Here’s some financial advice if you find yourself in your 20s and overpaid: spend your money. The first thing I did with my signing bonus was buy a fresh pair of Allen Edmonds (which I still have to this day), and then I drank the rest of it by taking visiting friends to Grand Central Oyster Bar for dirty martinis during lunch hour, figuring that the pointless corporate training sessions would go down easier if I lived out my Mad Men dreams. After all, summer in New York is intern season, where starry-eyed 21 year olds run around while the parents aren’t in town. “Your firm didn’t bring you out to Manhattan to stay at home and eat frozen Trader Joe’s” was an award-winning line that I used regularly to find company to join me at the St. Mark’s Ippudo. Getting in trouble and playing the character while I had nothing to lose is a mindset that has made me very, very content to just stay at the nice hotel and not seek unnecessary stimulation at this point.

In my brief time in the corporate world, I found out that institutional trading was, well, dead,

If you look at my nonexistent resume, it doesn’t seem real that I have as much institutional knowledge as I purport to have. But something that is necessary to understand is that “institutional trading” didn’t really exist for anyone trying to get into finance post-2010. Dodd Frank neutered everything that made the insane game of high stakes poker fun prior. Accordingly, I would walk into my MM final round interviews and boldly proclaim that their business would go under if they didn’t start taking delta risk. It seemed obvious — if everyone is competing for flow, and there’s no flow, how do you possibly make money? A VIX of 13 and a market driven by passive inflows means there’s no spreads to capture, and the pithy state of trading from 2010-2018 reflected this. Market-making profit is a fixed pool, and when times are good, firms open up. When times are bad, they compress — it’s fundamentally a sell-side service, and that’s probably how Citadel and Virtu came to rule flow. They were just better capitalized than everyone else to wait it out.

and I also realized that I just wasn’t cut out the sheer waste of time that white collar work is within a couple of weeks. (Indeed, I think I’m the only intern who has ever asked my desk neighbor whether anyone would mind if I quit.) What seemed totally insane to everyone back then (and probably still does to a lot of people reading this) was sort of a superpower of mine — I’ve just sort of understood when it’s time to walk away at the appropriate time my entire life

Being able to assess your skill accurately by ~18 is a superpower, a necessity to not waste your 20s by ~23, and a tragedy as to what the current school/corporate environment is doing to kids nowadays. We’re pushing this realization to people’s ~30s, and as a result, people who should have probably just settled and found a way to be happy feel robbed by the “economy” because they realize the upside of a steady paycheck isn’t just a guaranteed BMW and a million dollar house far too late.

My 2017 success led me to the delusion that I just might be able to make it trading on my own. Swimming in the online soup that led to weird information asymmetries convinced me that everyone I talked to that raved about “quantitative analysis” was just parroting something someone else had said. The Fannie trade convinced me that, if I looked wide enough, I could find all sorts of ideas in places people wouldn’t be able to keep up with through news articles and Excel.

Part of the fun of being self-taught is that you get to choose your own adventure. The player characters I chose to model my game after were Peter Lynch (who wrote one of my favorite books ever, One Up on Wall Street, which I summarize in this thread), Steve Cohen (who invented the information game that I play today, except my “insiders” are just people posting on X),

and the aforementioned Bill Ackman.

Reading the gossip about Ackman made me realize a lot of similarities in how I approached the world writ large.

In 1984, when he was a junior at Horace Greeley High School, in affluent Chappaqua, New York, he wagered his father $2,000 that he would score a perfect 800 on the verbal section of the S.A.T. The gamble was everything Ackman had saved up from his Bar Mitzvah gift money and his allowance for doing household chores. “I was a little bit of a cocky kid,” he admits, with uncharacteristic understatement…

[H]e was the kind of hyper-ambitious kid other kids loved to hate (whoof, do not interview my fellow interns ~ed.) and just the type to make a big wager with no margin for error. But on the night before the S.A.T., his father took pity on him and canceled the bet. “I would’ve lost it,” Ackman concedes. He got a 780 on the verbal and a 750 on the math. “One wrong on the verbal, three wrong on the math,” he muses. “I’m still convinced some of the questions were wrong.”…

Extreme conviction to the point where it’s the world that’s wrong, not you, sounds like a textbook case of delusional narcissism. (And I’m not saying that it isn’t.) But when you are playing cerebral games with intense pressure, that kind of delusion is almost the only way you can reliably perform at the highest level. I share his habit of being overly verbose to explain my own thoughts, but you’re not going to be able to talk me out of my convictions. (Thankfully, I haven’t hit such a rate of success that I’m totally immune to admitting I’m wrong before smashing into a divider.)

Another similarity is that, if something makes intuitive sense, I’ll make a snap judgment, which can blow up spectacularly, but also is a sign that you’re capable of a leap of faith:

Let’s talk about lunch for a moment, because there’s a pretty good story about none other than Bill Ackman making, let’s say, a rather large investment on a whim back in 2016:

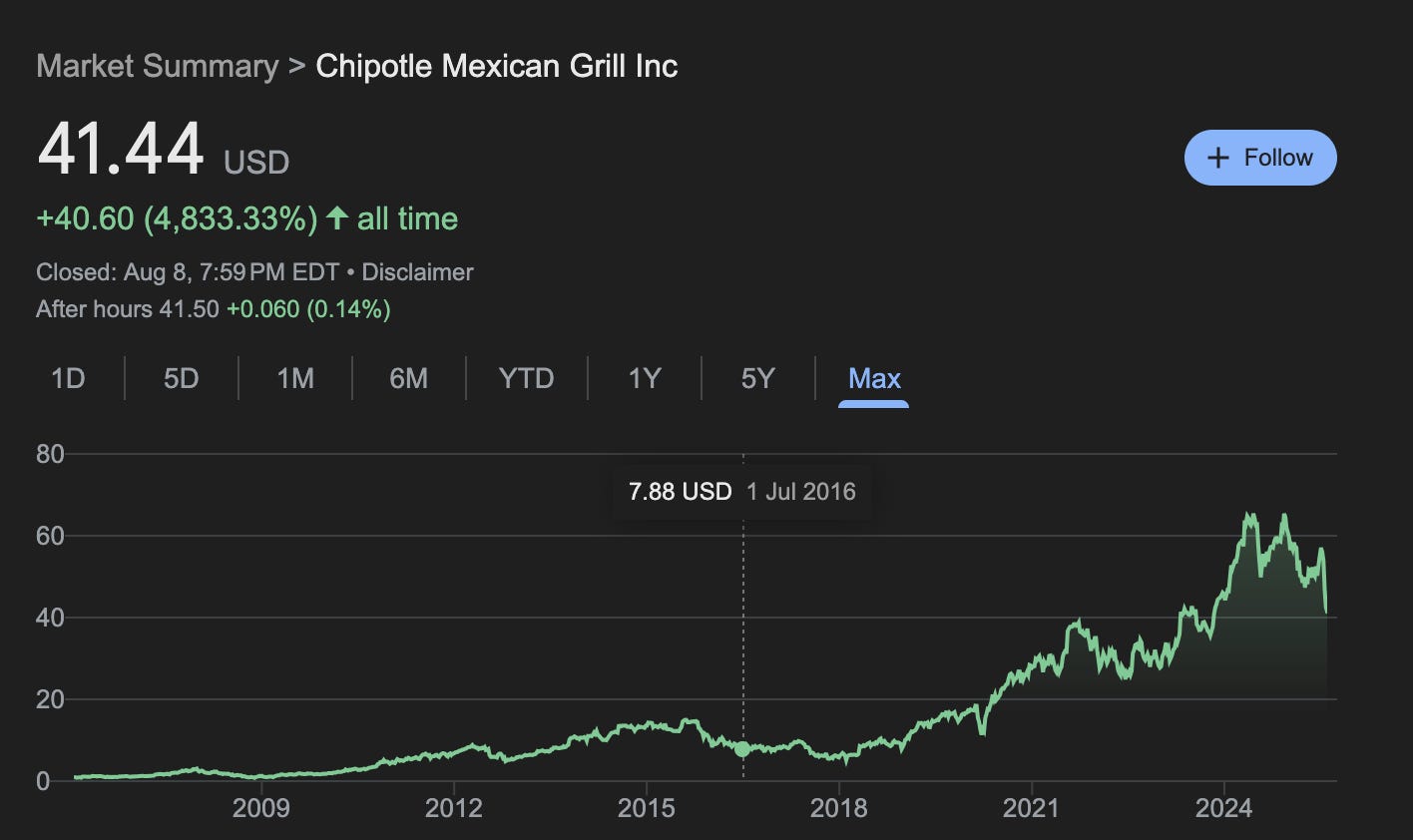

Mr. Ackman’s Pershing Square Capital Management acquired the option to purchase 2.9 million shares, which represents a 9.9 percent stake in Chipotle, according to a regulatory filing on Tuesday…

Shares of Chipotle have plummeted more than 40 percent over the last year after hundreds of people got sick after eating in its restaurants. A majority of the illnesses stemmed from norovirus contamination and strains of E. coli and salmonella.

The scandal has caused sales to slump, as customers stayed away from Chipotle restaurants out of fear of getting sick. Revenue during the quarter through June declined 17 percent, while comparable restaurant sales decreased 24 percent, the company said in its earnings report on July 21.

Ackman has made some pretty interesting decisions involving Chipotle, some of which definitely got him into trouble. Here’s an old anecdote about another snap judgment:

Years before Valeant became Ackman’s white whale, he was hanging out with the company’s then-CEO Michael Pearson at the drugmaker’s HQ, contemplating lunch. The chicken and salad in the cafeteria didn’t impress the hedge funder. “But they had a Chipotle around the corner,” Ackman recalled in 2014. “I actually asked if I could get a Chipotle burrito.”

Pearson’s gofer dutifully obliged. But when they sat to eat, Ackman got a surprise. “Mike walked into the conference room and asked me for 20 bucks,” he said. It was at that moment, a wad of half-chewed burrito hanging out of his mouth, that Ackman’s faith in Pearson was solidified. (The fact that the CEO was such a tightwad evidently convinced Ackman him that Valeant was “allocating its capital intelligently.”)

Ackman shoved a ton of his gains on the Allergan hostile takeover in support of Pearson (more on Valeant another day, as it’s one of my own “gut feeling” big shorts I’ve ever taken in my life), and we all know how that ended:

Perhaps in search of redemption — after all, Pearson was the problem, not his burrito — Ackman took a leap of faith. “I like the burritos” was a precursor to “I like the stock”:

Bill Ackman is hungry for Chipotle and everyone is piling on. “We are unclear if Pershing Square can add value,” analysts at Baird wrote, a day after Ackman’s Pershing Square bought up a 9.9 percent stake in the burrito chain, which is ailing from multiple disease outbreaks in last year.

Stifel was less forgiving: “We cannot fathom Pershing's operational or mathematical investment thesis.”

But there’s a simpler take here: Bill Ackman just likes Chipotle burritos. He doesn’t have some baroque hypothesis for how to wring value out of the company, as with his disastrous investments in Valeant and Herbalife. This one seems different. And that's not a bad thing.

Lo and behold:

Similarly…

Betting big, in a sense, is the only thing I’ve ever known how to do. I was sure the girl at the end of the hall freshman year was “the one”, I was convinced that I could generate more value betting on myself than the long-term value of a degree and a resumé, and I was convinced that there was no reason to keep Fannie and Freddie under conservatorship. There’s simply no reason why so many smart people like myself are sitting around doing all sorts of random things to generate income as opposed to being plunged into processes and trying to make them better. In a sense, my time is gone — you can’t just fix broken systems by promoting 20s types with parallel competencies like hypergambling, mass information processing, SaaS building, and so forth, which is why DOGE was an accidental success rather than a program with any real chance of reforming the government.

So when I see “motivational” commentary like this, I think it largely misses the actual way “betting big” works.

If you're actually going for it, you don't get time to reflect on any meaningful scale. That leap of faith in 2017 has only really come to fruition in the past year. You don't become bitter with age, you just age and choose whether or not to wallow in regrets or to keep looking forward. The proper way to swing big is to be brutally honest about your own capabilities, work for free (usually alongside an income stream, I wouldn’t recommend doing what I did) until you cannot do both concurrently and must pick a pathway. That is when you "just do things": after you've meticulously planned out the variable pathways.

Perfect recall is mostly a curse. I remember every missed trade, every panicked reaction, every cringeworthy text, every embarrassing moment of my life. Living with regrets is a choice, and I choose to avoid doing so by being sociopathic about compartmentalizing them. I’m pretty sure that acknowledging the collective cognitive dissonance would literally kill me at this point.

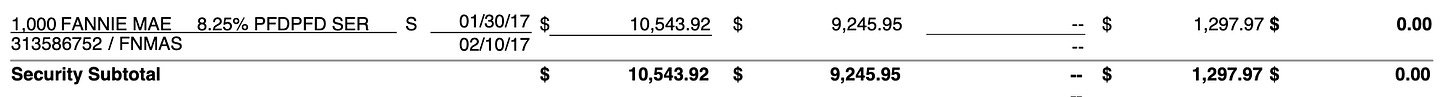

But you never know when a piece of information will be monetizable, and unlike an LLM black box, I know exactly what’s relevant at the appropriate time. The day after the election, I immediately went back to Fannie and picked up some preferreds.

I was never any good at getting over exes anyway (and it’s why I don’t watch Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), and apparently Bill didn’t forget either.

I woke up the other day to a ton of alerts, however,

and found out that, after nearly 9 years of watching this trade, that the earnings belong to Fannie (and Freddie) are going to be unlocked immediately. There is something surreal about knowing that the idea that sent me down the ungodly rabbithole of reading appointments-related admin law and essentially picking up a securities law specialization in the process is actually going to play out — that the trade that perhaps started this whole arc all was the right play all along and it could be arrived at through your own cognitive considerations.

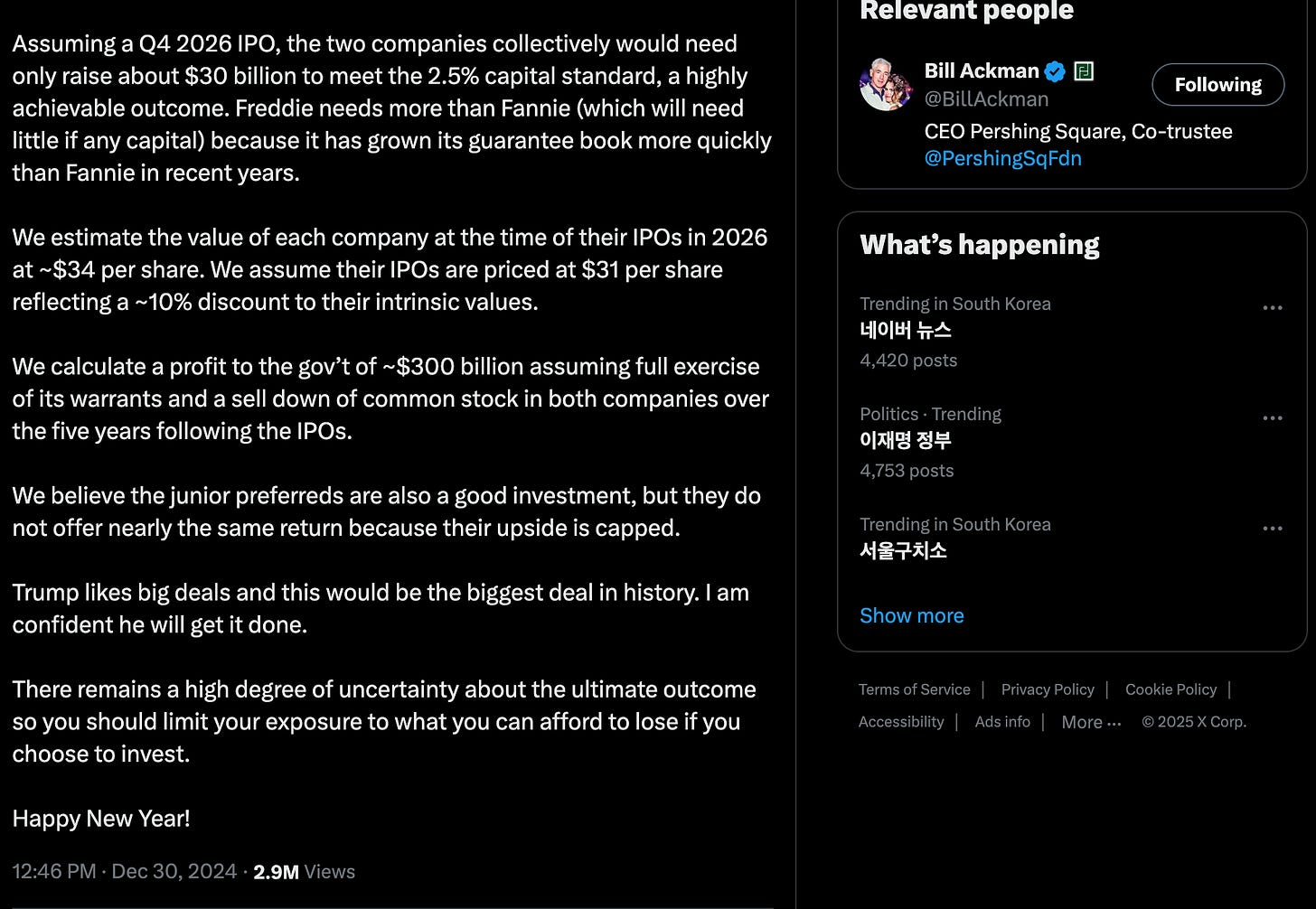

(For some scenarios on how this could play out, you can read Ackman’s analysis directly or Levine’s Money Stuff. I truly don’t know where this goes, it’s unprecedented territory.)

I often talk about how “I told you so” never feels as good as you think it will, but this case is a rare exception.

It’s less about the logic or the profit itself, and more the fact that this is the longest I’ve ever waited to be validated on an idea. I’m reminded of an excerpt from a piece of fiction I wrote for my freshman year seminar:

…I still maintain that, yes, you made the wrong call, but wrong isn’t absolute. It’s a fair point in that it’s not a lack of intelligence that keeps me behind; it’s my tendency to compare myself to everyone but myself. Does the heroin addict ever see himself as such, or is he just concerned with getting to the next needle? Likewise, could I have ever seen myself as a failure when what I am really is just me? I don’t know where I can go with this, but this failure is hopefully the beginning of an acceptance that disagreement is not an insult to my intelligence but rather an outsider’s way of building me up, that could only be thought of as the first step to happiness.

Trading forces you to reflect on the question “would you rather be profitable or right?” almost daily. In the end, you can’t forcefully impose all of your correct ideas on the world, because a block button exists. There’s no rigorously logical methodology to the court system, and she can just block your texts after a certain point so you can’t continue to make your case. Similarly, life offers the question “would you rather wait or be happy?” The trick is to realize that, well, you can just unblock yourself.

Epilogue

I did, in fact, recently see the girl that was down the hall and to the left 11 years ago. Perhaps my judgment at 17 was far, far better than I thought. Anyway, that’s a story for another time.