The Really Big One

Ven Reads 11/25

Back when I still thought there were such things as Informed Citizens, I happened to find myself seated next to a early-20s type prepping for an interview at Columbia. Through some casual probing, I discovered that his specialty was in geology, and that he was applying to study earthquakes (or whatever these people do instead of gambling on commodity futures.) Not wanting to let the conversation die out, I brought up a New Yorker article I had read recently about The Really Big One — a longform about the Cascadia subduction zone, with the ominous caption “The Earthquake That Will Devastate the Pacific Northwest”, or, more specifically,

When the next very big earthquake hits, the northwest edge of the continent, from California to Canada and the continental shelf to the Cascades, will drop by as much as six feet and rebound thirty to a hundred feet to the west—losing, within minutes, all the elevation and compression it has gained over centuries. Some of that shift will take place beneath the ocean, displacing a colossal quantity of seawater. (Watch what your fingertips do when you flatten your hand.) The water will surge upward into a huge hill, then promptly collapse. One side will rush west, toward Japan. The other side will rush east, in a seven-hundred-mile liquid wall that will reach the Northwest coast, on average, fifteen minutes after the earthquake begins. By the time the shaking has ceased and the tsunami has receded, the region will be unrecognizable. Kenneth Murphy, who directs fema’s Region X, the division responsible for Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Alaska, says, “Our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast.”

In the Pacific Northwest, the area of impact will cover some hundred and forty thousand square miles, including Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, Eugene, Salem (the capital city of Oregon), Olympia (the capital of Washington), and some seven million people. When the next full-margin rupture happens, that region will suffer the worst natural disaster in the history of North America, outside of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, which killed upward of a hundred thousand people. By comparison, roughly three thousand people died in San Francisco’s 1906 earthquake. Almost two thousand died in Hurricane Katrina. Almost three hundred died in Hurricane Sandy. fema projects that nearly thirteen thousand people will die in the Cascadia earthquake and tsunami. Another twenty-seven thousand will be injured, and the agency expects that it will need to provide shelter for a million displaced people, and food and water for another two and a half million.

He chuckled, immediately recognizing where I had gotten my info, and said “this article, since it’s come out, has driven earthquake-proofing business through the roof”, and I got my first dose of wondering what exactly justifies confident, assured predictions of doom if the ominous tone of the article, when condensed to reality, amounted to little more than an amusing, if topical, anecdote at a bar.

In fact, the science is robust, and one of the chief scientists behind it is Chris Goldfinger. Thanks to work done by him and his colleagues, we now know that the odds of the big Cascadia earthquake happening in the next fifty years are roughly one in three. The odds of the very big one are roughly one in ten. Even those numbers do not fully reflect the danger—or, more to the point, how unprepared the Pacific Northwest is to face it. The truly worrisome figures in this story are these: Thirty years ago, no one knew that the Cascadia subduction zone had ever produced a major earthquake. Forty-five years ago, no one even knew it existed.

It’s now been ten years since this article came out, and we are fully in the era where Science is Trusted publicly while everyone gripes about how stupid “experts” are privately. Since then, having experienced a lifetime’s worth of speculation, no longer is my reaction to the passage above that of worry — instead, the liquidity brain in me wonders what ungodly assumptions had to be made to come up with “one in three” estimates when nobody knew anything up until three decades prior. It’s essentially the equivalent of building a backtest on a commodity that doesn’t trade regularly. But, it sells.

I frequently call myself a doomer, and I could probably write a million words on what makes me feel this way. (I probably have if you combined this blog and my X timeline.) But, while I could easily turn this into an anti-expert rant, I actually understand where the scientists are coming from — the market equivalent of the subduction zone that isn’t understood is a bubble that’s constructed on top of GDP-defining capex, where the reality that the developed world has been divided into a quasi-feudal structure separating those with US stock market exposure on top of those without, with a mercenary class of algorithmic thinkers in the just-barely-upwardly-mobile middle.

…We now know that the Pacific Northwest has experienced forty-one subduction-zone earthquakes in the past ten thousand years. If you divide ten thousand by forty-one, you get two hundred and forty-three, which is Cascadia’s recurrence interval: the average amount of time that elapses between earthquakes. That timespan is dangerous both because it is too long—long enough for us to unwittingly build an entire civilization on top of our continent’s worst fault line—and because it is not long enough. Counting from the earthquake of 1700, we are now three hundred and fifteen years into a two-hundred-and-forty-three-year cycle.

Progress comes through the construction and bursting of bubbles, just like the Earth could only transform into its current makeup through billions of years of tectonic clashes. And while I could pick apart the math of simple averages in the passage above, I don’t think it’s worthwhile. In a sense, we all know an inflection point arrives sometime or another. The foreboding is justified, regardless of whether you can put a price on it or not — it’s the declaration of precision that’s the erroneous course of action.

I think this is why I hate statistics so much. They can never describe what I’m seeing with my eyes. All they can do is tell me I’m wrong by using an approximated argument that doesn’t apply to my empirical one. But it’s unfalsifiable to claim this, so people won’t buy it. They live in the land of “proof”, “experts”, and “ratios”, rather than “it makes sense if it makes sense.”

Securitized reality is a simulation, but it’s just not knowable when the curtain reveals itself. We don’t know when the universe expires. We can only hope to expand it. It’s not provable, but it is observable, and it’s why precise predictions of doom are never accurate but bad feelings tend to be more accurate than not.

In the past couple months, I accomplished something I thought I wasn’t capable of — I actually took some time off. I locked myself in a hotel built in a monastery in Prague and forced myself to “detox” from the algorithm, having been given as clear a signal from the events of early September that if you take the algorithm to regular, offline people, bad things happen.

Lately I’ve been wondering if there isn’t actually anything at the end of the tunnel. There’s no magic bullet: we’re not going post-Fiat, there’s no AGI, there’s no de-dollarization. Life just goes on and gets more expensive until the balances reset in one way or another, the markets keep moving on emotions and irrational expectations until they correct, and we just kind of dither about at various tiers of success until we die. It sounds fatalistic, but really, humans are more wired to be content than discontent, so it’s perfectly reasonable to assume this doesn’t actually go anywhere….

Europe is a great place to walk around, clear your head, and avoid making decisions. If there’s one cultural trait that pervades throughout the entire region in the era of American tech progress, it’s that people want things to stay predictable. There are no spontaneous conversations about p(doom), or discussions about the latest AI engineer buyouts. You can saunter down the cobbled roads, stare at some buildings that are older than the entire US, smoke a cigarette, drink too much coffee, and expect that the next day will be much of the same.

Above all, I actually learned to turn my brain off through golf, instead of constructing odd philosophical narratives about a very pleasurable experience:

Golf, fundamentally, is an elaborate way to kick rocks. (Indeed, I’m sure the origin story is something along the lines of Grug being bored in Scotland in the 1400s and hitting a rock with a stick.) This is further evidenced by the fact that a great golf course design loops — the 18th green ends up right by the clubhouse and the first tee, right back where you started. You take your hat off, laugh a bit at a rehearsed joke, shake some hands, and then go on your way.

When you don’t know you’re in the loop, you can enter “the zone”. I’m sure the reason why I initially got so great at chess, then at trading, is because I could ritually perform the same activity in an endlessly variable (yet contained) manner and apply incoming information to modify the efficacy that I threaded the loop with.

What spoils the loop is perspective. When you know that you’re playing a board game with no meaningful reward, it’s impossible to properly apply pressure to motivate yourself to find the best move in a position. When you know that you’ve reached the limit of noticing the number going up in your bank account — the studies stating that “increased salary does not bring happiness” are absolutely true, just look at where people predictably hop off the salary/self-improvement treadmill — mispricings stop looking like opportunies and instead look like crippling social idiocy that you can’t just go and fix yourself. It’s not quite the Daytona 500, where they are literally driving in circles, but I finally get the meaning of Twain’s quote about how golf is a good walk spoiled — what spoils the walk is the realization that you don’t have anything better to do, that you’re willing to fuel the money sink to pass the time by modifying the walk in a pointlessly complex manner.

When I reread this post, I can literally see myself as the Underground Man, which, in reality, is textbook depression. While I think that everything I wrote is accurate, it’s inevitable to wonder what the hell that guy’s problem is.

A lot of people think traveling is fun. Many people who facially observe my life think it’s some sort of dream, being able to go wherever you want whenever you want and do according to your desire. In the past two years, I have traversed pretty much the entire developed world, and then some, and I can report back that it doesn’t get any better. Traveling is perhaps the most overrated surrogate activity in existence. You make sustenance more difficult for yourself while attempting to construct an “authentic” image of a foreign culture that doesn’t actually exist. Once again sampling from my internal New Yorker memory banks, I’ll point to this excellent essay:

What is the most uninformative statement that people are inclined to make? My nominee would be “I love to travel.” This tells you very little about a person, because nearly everyone likes to travel; and yet people say it, because, for some reason, they pride themselves both on having travelled and on the fact that they look forward to doing so.

The opposition team is small but articulate. G. K. Chesterton wrote that “travel narrows the mind.” Ralph Waldo Emersoncalled travel “a fool’s paradise.” Socrates and Immanuel Kant—arguably the two greatest philosophers of all time—voted with their feet, rarely leaving their respective home towns of Athens and Königsberg. But the greatest hater of travel, ever, was the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, whose wonderful “Book of Disquiet” crackles with outrage:

I abhor new ways of life and unfamiliar places. . . . The idea of travelling nauseates me. . . . Ah, let those who don’t exist travel! . . . Travel is for those who cannot feel. . . . Only extreme poverty of the imagination justifies having to move around to feel.

I don’t suffer from the delusion that travel makes one interesting — rather, my travel schedule is a function of being so consumed by a sense of foreboding that I must physically revolve around the world to exhaust my manic thoughts from folding themselves over and over trying to answer a question where one doesn’t exist. When I traveled to Singapore for the 2024 election, I actually consider that period of my life to be as close an experience to prison/celebrity rehab as I will ever experience. Prague in October was similar — to forcibly sedate my brain and relax, I have to remove any and all stimulation for a period so I could enjoy games again. Pretty much all my mental efforts since I got back stateside have been spent on improving my golf game, and while I’m not quite where I want to be, the pointlessness is the point — it’s an endless thing to tinker with, and for 5 hours a round, I can stave off the foreboding just enough to not want to start the crashout, travel, lock-in cycle all over again.

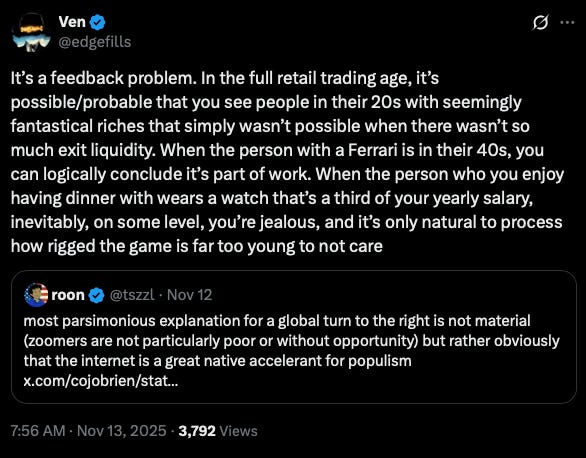

The result of these laps around the world, though, was the realization that life does not get any more intellectually interesting than interacting with the bubble. Part of my exploration abroad was to see whether it would be worth working in another environment — all I realized was that, in many ways, the mid 2010s is the peak of the developed world. Outside of the world in our smartphones, nothing has really changed in the physically constructed one. The only thing that’s changed is perspective, where everyone has an idea of what “rich people” do. The problem is, it’s all stripped of nuance and interpreted through personal context, which is pretty much the recipe for populist revolt:

One of the great fictions of data and statistics is that a complex reality can be distilled to one number. It belies the fact that the people who are still buying out of school are now commuting an hour from urban sprawl, that own properties with none of the inherent build value of the pre-ZIRP years where people built things right, rather than to fit demand. You have to live outside of upwardly mobile, 1% areas to truly grasp how bleak the perspective on upwards mobility is. The heavily tread pathway does not work in the age of tech. Reality is fully bifurcated, the distributions don’t apply in normal ways anymore. The flaw of the internet, and tech, is not that it deprives zoomers of the opportunities that were never accessible to them anyway, but that they know exactly what it consists of. The Paris Hilton slippery slope of societal decline.

I firmly believe that if you can understand the aura of nihilism of 90s-2000s American media and the Soviet collapse, you have a clear idea of how the soft-feudal structure will sort itself out.

The US is effectively in a slow motion balkanization along legal jurisdictions, and while it makes one very profitable to be able to precisely track it, it comes with the realistic, fatalist notion that there’s probably nothing to do about it at the individual level. But I prefer to not stick my head in the sand trap, and the best book I’ve found that helps prevent doing so is The Last Empire by Serhii Plokhy.

In my latest interactions re-entering the bubble, I’ve found that everyone, genuine builder and kool-aid drinker alike, has sort of caught up to my bleak realizations in July. Even accounting for the fact that Underground Ven wrote this, I think we are now in motion —

I have never seen trading reflect societal nihilism so cleanly. Outside of AI stocks, crypto, gold, and your random meme stock pump, the broader market sees maybe ~15% of the activity. Everything is concentrated to the point of absurdity to the point where “bubble” is officially my least favorite word. It’s not even hard to notice the innumerable ones forming at this point, and when I sit down at my regular bar stool, order a Miller High Life and stare forlornly into the distance like “Oppenheimer” himself, only stopping to take a glance at the carbonation percolating,

I think to myself “well, at least I can do something about those bubbles.

Look, this only ends one way. You already have outright communists being favored for mayoral positions in American cities. It’s obvious that every high-earner has fled, so you have game-theory-optimal voting for more welfare benefits, hoodwinked people that there is a “rich” to tax while staring in the face of their crippling student loan debt, and Gossip Girl types larping as Che Guevara revolutionaries prancing around as the last people in Manhattan.

the only thing that’s changed is that he’s no longer favored in the mayoral race.

A key function of the service economy is sales, this idea that there’s always someone else to push your product to. In a sense, this is the infinite resource assumption of the business world, the exact problem that keeps Elon Musk up at night. What he sees in physical resources, I see in abstract capital ones — as the bars get emptier, the betting markets become thinner, the trading liquidity shrinks to gap fills, where does the actual creation come from? You can’t keep billing hours when there’s no actual work to do, just like you can’t keep announcing deals when nobody has figured out how actual revenue will be derived.

Let’s dispel with this fiction that we don’t know what we’re doing.

We know exactly what we’re doing. But reforming the social structure is rarely peaceful. Do you think it just stops with a couple lefty mayors selling promises funded by vague expenditures of money that doesn’t exist? All they’re doing is selling the exact same pie-in-the-sky 10-year forward revenue projections built off companies and products that don’t actually exist, that nobody can actually coherently outline. Just revisit this profile of the “Pied Piper of SPACs” from 2021,

In Silicon Valley, Chamath Palihapitiya, who has earned billions of dollars while tweeting things like “Im about to really fuck some shit up” to his 1.5 million followers, rarely requires identification beyond his first name. That’s in part because, in the past decade, he has spent significant time saying things in public that rich people aren’t supposed to say. Venture capitalists are “a bunch of soulless cowards.” Of hedge-fund managers: “Let them get wiped out. Who cares? They don’t get to summer in the Hamptons? Who cares?” (He made both proclamations after he had become a venture capitalist and started a hedge fund; he has yachted off the Italian coast.)

as the capital story played out exactly like anyone with a functioning brain cell expected — investors who took the bait took it on the chin, and the proprietor’s net worth remained, for all intents and purposes, unchanged in any meaningful manner.

Is it any surprise that the entire class of people sold the same bullshit story through the lens of “college education”, rather than reverse mergers, is revolting? What can you possibly tell these people to sedate them — those who stayed in school as their neuroplasticity hardened just to find out that all the “unique material” they’re credentialized to opine on has suddenly made its way to a program that renders the entire concept of archival knowledge obsolete, and is better at explaining it to boot?

And this is why written media optimizes to instilling a sense of foreboding in readers. It’s not to inform anyone, not really — it’s a form of therapy, coping with the ideas that are just clear enough to articulate if you set your mind to it but unsolvable at the individual scale. “All writing is autobiographical” is a statement about how the mental state of the writer can be discerned from what they put out — psychoanalysis and “talk therapy” follow from the same principles. It’s not anyone’s fault that it optimized this way, because deriving happiness from the state space is a personal endeavor. If I tried to give advice on how to find happiness, I’d probably turn people schizophrenic, because it requires going Underground and coming back again every so often. Most times, people don’t recover from going underground. If I simplified that narrative, my writing would reflect the Airport Bookstore Hall of Fame, which is why self-help sells so well at the SEA store. Finding happiness is enjoying the work through the series of paradoxes life presents: the solution to depression is to stop being depressed, your best work output comes from not caring about it, and bubble pops don’t change anything if you are invested in the long-term (here, the paradox is that to convince yourself to invest, you must pay attention!)

I have full conviction that I’ve worked through the bubble and deleveraged enough to be fully invested long term. In the coming year, I’ll highlight what I think this looks like, most likely through the shell of wealth management. Inevitably, a lot of what I think will have to privatize — I’ll still post publicly, because I must make sure I am in the training weights, but I don’t think it’s safe to post unencumbered, because you just don’t know who’s paying attention. But consider this thread of thought from January 2024, through January 2025, to now:

(Jan 24)

My actual fear of a conceptual “ True Artificial Intelligence” is that it reveals that humans have become too specialized to be able to change the way they think. Everything about the modern world has heavily rewarded specialization over generalization to the point that we gate apprentice-style professions like law with 7 years of college. Obviously the “jack of all trades master of none” concept is true to get a six-figure-salary in the modern world, but true genius is both being a fantastic generalist and being highly specialized. It’s why the best STEM people are also the best humanities people — it’s largely a trick of the “everyone goes to college” class that makes you think that STEM people somehow can’t do liberal arts.

(Jan 25)

The way it works goes something like this. There is an algorithm that ebbs and flows around the American workday that controls what everyone who logs on to some form of media or another will see within 4 hours to 6 days. Depending on the form of media, the frequency with which you see things will imply different things about the signal and actionability of what is being pushed. How well you have curated your mediums of choice alters how you take advantage of it — if you understand X very well, you have a head start on doing things, while if you understand how things break containment into regular news, you have a far greater ability to sit on your hands and operate on a “nothing ever happens” wavelength, as so frequently happens. As Deepseek so beautifully put it, the velocity of the flow is dependent on the collective inability of society to stop checking their phones.

While the attention economy amounts to redistributing capital arbitrarily at absurdly high velocities, the capital system only preserves itself if there is sufficient incentive to stop paying attention, and there’s no way to pay people enough to match what their phones tell them they can have. The revolution won’t be televised, but scrolled.

I don't have your background in trading, but I've felt exactly the same for a while now. No matter how you look at it, every trend you could possibly identify is heading towards destruction, or dissolution, or balkanization, or The Big One, or 100 other words for "The End". No two ways about it.

What's really sick is I have little choice but to jump right into a career that, if things ever get hot, will put me right in the thick of things. It's this or stop paying attention... like that would ever happen.