The Land of Confusion

Part 1

A tidbit that perhaps betrays my age — I must confess that the distinction of Genesis pre- and post- Peter Gabriel doesn’t matter all that much to me, though I don’t quite share my fellow financier’s love for Phil Collins’ solo career.

Something that changed quite dramatically post-2020 was that I no longer required a crippling hangover to enjoy a Dan Brown novel, I started looking forward to watching “Mission Impossible” in theaters, and I became genuinely fond of simple procedural shows with solid, glamorous casts and quick quips like Burn Notice or The Mentalist. I developed a rather significant distaste for shows that had to point out the plot holes, with cynical, irony-poisoned, “everything and everyone is shitty” narratives that shows like Succession exemplify best. I’m sure in the age where viewership of music videos congregated around MTV, rather than YouTube, songs like Land of Confusion or Amerika, the lyrics and narratives propagated felt genuinely insightful. But in the age where an insightful post maybe lasts in my head long enough to quote before moving on, I can’t help but look at comments like this and cringe.

Spoiler, it’s always going to be relevant because it cast a wide enough net in terms of commerciality, and nobody forgets what they listened to in their teens and 20s. (Indeed, the shift towards mainstream popularity was precisely the main critique of the Phil Collins-led iteration, which is also why Bateman’s adoration of Sussudio is perfectly on brand.)

And, of course, there’s a political note to be made here — as I noted at the pico bottom of the April tariff drama,

I myself witnessed boomers at what was ostensibly a college progressive middle east rally holding “Down with Elon” signs like it was a Grateful Dead concert. They don’t even know why they’re mad about Sunday night futures movement, just that they’re told to do so.

the algorithm is enmeshing Palestine with Palantir, threading together narratives in such a wild fashion that thematic ETFs simply can’t keep up.

But instead, I’m more curious as to why I enjoy these shows now. I didn’t watch them as they aired — I was very much ingrained in the “prestige TV” era where HBO and AMC ran the world. Maybe the closest thing to a “formula” show I watched in real time was How I Met Your Mother. My reaction back then, if someone said that their favorite show was Bones, would be akin to meeting someone today who’s really into Tim Allen’s latest sitcom (yes, he’s still on TV.) Why would you possibly find it engaging?

And yet, humans are creatures that take delight in pattern recognition — when people recognize a song on the radio

In a sense, great lyrics and songs are about pattern recognition — the way people find “meaning” in songs is a function of the artist generalizing a personal anecdote into a relatable one.

and apply it to, say, their interpretation of the news headlines they read, or their profession, this brings repetitive internal joy. (“As topical now as it was 40 years ago.”) Ditto for a sudoku or crossword puzzle, as The New Yorker so terribly put it:

In “From Square One,” a literary meditation on crossword puzzles, the writer Dean Olsher describes the practice of solving them as “a habit, like smoking.” In myself I see it more bluntly: it’s an addiction (also like smoking). I couldn’t stop even if I wanted to, so it’s fortunate that I don’t. The gridded expanse of black and white soothes and thrills me. I crave the velvet dissociation of turning off my usual cognitive Abstract Expressionism in favor of the specific rhythmic mental state of solving: building momentum and settling into the satisfying intellectual cycle of clue and solve, clue and solve.

Solving formulaic TV show plot points, while still relishing in the little mysteries — how exactly is Tom Cruise going to win this time, what tiny detail did Patrick Jane notice that tipped him off on where the hidden diamonds are — is a pretty similar activity. But most importantly, it’s a human activity — I am 100% certain that an episode that aired in 2008 is a human-constructed labyrinth that isn’t particularly mentally intensive to work through, but also isn’t idiot-checking me the whole time like modern Netflix shows do:

Executives are pushing writers to develop simpler, less complex scripts to keep distracted viewers engaged, according to N+1 magazine. Multiple screenwriters report that company executives are sending back scripts with requests to narrate the action, such as announcing when characters enter the room.

Netflix knows we are on our phones all the time, with as many as 94% of people tinkering on their devices while watching TV, according to a 2019 study commissioned by Facebook. Dumbed-down scripts that lack nuance and visual cues can help viewers with divided attention follow along, making them less likely to turn the program off.

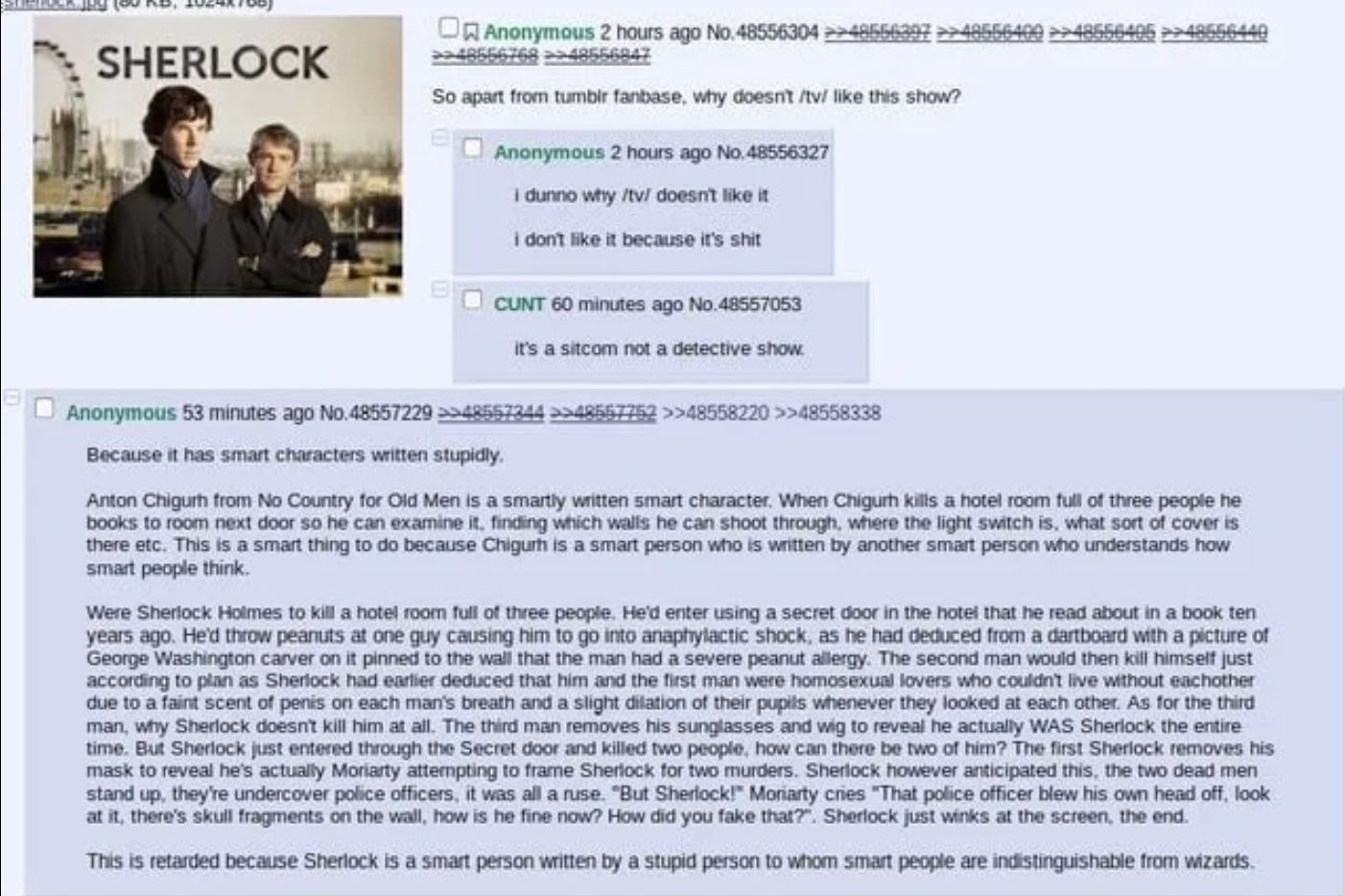

And there is a real art to it. There are good and bad versions of this — I don’t need the actual resolution of the crime through prosecution to make any sense. The bowtie on top is fine. What I have a problem with is stupid constructions of “smart” characters, as the classic /tv/ post describes:

But more than anything, it’s nostalgia. There was actual effort across the board that went into these productions, from a character actor making a good living doing bit parts, or knowing how to not deviate too far from a trope. Tropes are good, formulas work — the latest F1 flick is a textbook example of how to execute — but in the age of tech, the prioritization of engagement over a genuinely caring construction of the tapestry is probably going to permanently shift what content we consume. For example, take this hypothetical Mentalist episode that Grok ripped out in about 10 seconds:

In a sense, this is terrifying — it’s clever, topical, remains true to the gist of the show, and even comes up with a signature quip. Compare this to current-day South Park, a show that is desperately trying to stick to its tried-and-true “six days to air” method of remaining relevant, and failing to generate anything beyond the humor of a well-constructed X thread. It’s a near-certainty that the drafting and editing process is going to rapidly shift in the next few years, and it won’t be clear what the “human” part of production is.

Figuring out whether something is AI or not, however, is a ludicrously unfun labyrinth to work through, as Sam Kriss delightfully elaborates:

In the quiet hum of our digital era, a new literary voice is sounding. You can find this signature style everywhere — from the pages of best-selling novels to the columns of local newspapers, and even the copy on takeout menus. And yet the author is not a human being, but a ghost — a whisper woven from the algorithm, a construct of code. A.I.-generated writing, once the distant echo of science-fiction daydreams, is now all around us — neatly packaged, fleetingly appreciated and endlessly recycled. It’s not just a flood — it’s a groundswell. Yet there’s something unsettling about this voice. Every sentence sings, yes, but honestly? It sings a little flat. It doesn’t open up the tapestry of human experience — it reads like it was written by a shut-in with Wi-Fi and a thesaurus. Not sensory, not real, just … there. And as A.I. writing becomes more ubiquitous, it only underscores the question — what does it mean for creativity, authenticity or simply being human when so many people prefer to delve into the bizarre prose of the machine?

If you’re anything like me, you did not enjoy reading that paragraph. Everything about it puts me on alert: Something is wrong here; this text is not what it says it is. It’s one of them. Entirely ordinary words, like “tapestry,” which has been innocently describing a kind of vertical carpet for more than 500 years, make me suddenly tense. I’m driven to the point of fury by any sentence following the pattern “It’s not X, it’s Y,” even though this totally normal construction appears in such generally well-received bodies of literature as the Bible and Shakespeare. But whatever these little quirks of language used to mean, that’s not what they mean any more. All of these are now telltale signs that what you’re reading was churned out by an A.I.

There is an effort to categorize “AI” styles — emdashes are one of them, much to my chagrin as someone who loves using them, because that is how these models anchor their sentences from running wild due to compounding probabilistic noise — but as someone who has read more than virtually everybody, it’s not really a sign that I look for. Rather, it’s an acute kind of pressure where it feels like I’m parsing something to look for key points, but instead of getting an intuitive grasp of the writing, I receive an almost acupressure-like feedback instead.

I don’t need to elaborate on this — Kriss says everything I think I’d care to write about style. What’s much more insidious is when the text-generation unlocks a pattern-matching reward mechanism through interpreting the text. The same crossword clue velvet cognitive abstract expressionism whatever the fuck turns into overinterpreting output, generating further and further tendrils that wrap around an interpretation of reality that’s entirely centered around what you expect to find out.

The modern term is “AI psychosis”, but really, it’s nothing new — the way brains operate (and what LLMs are constructed to imitate) has a solved, hackable reward mechanism. Positive and negative reinforcement operate as stabilizers of a directed pathway prompted by a variable reward mechanism. Or, as Nabokov puts it in his excellent short story Signs and Symbols,

The system of his delusions had been the subject of an elaborate paper in a scientific monthly, which the doctor at the sanitarium had given to them to read. But long before that, she and her husband had puzzled it out for themselves. “Referential mania,” the article had called it. In these very rare cases, the patient imagines that everything happening around him is a veiled reference to his personality and existence. He excludes real people from the conspiracy, because he considers himself to be so much more intelligent than other men. Phenomenal nature shadows him wherever he goes. Clouds in the staring sky transmit to each other, by means of slow signs, incredibly detailed information regarding him. His in- most thoughts are discussed at nightfall, in manual alphabet, by darkly gesticulating trees. Pebbles or stains or sun flecks form patterns representing, in some awful way, messages that he must intercept. Everything is a cipher and of everything he is the theme. All around him, there are spies. Some of them are detached observers, like glass surfaces and still pools; others, such as coats in store windows, are prejudiced witnesses, lynchers at heart; others, again (running water, storms), are hysterical to the point of insanity, have a distorted opinion of him, and grotesquely misinterpret his actions. He must be always on his guard and devote every minute and module of life to the decoding of the undulation of things. The very air he exhales is indexed and filed away. If only the interest he provokes were limited to his immediate surroundings, but, alas, it is not! With distance, the torrents of wild scandal increase in volume and volubility. The silhouettes of his blood corpuscles, magnified a million times, flit over vast plains; and still farther away, great mountains of unbearable solidity and height sum up, in terms of granite and groaning firs, the ultimate truth of his being.

Thus, we realize the root of the infohazard is not determining whether or not something is artificially generated, but whether it is describing something tangibly real. Searching for solutions to the Millennium problems in mathematics — questions that have never been answered before, even when attempted by the greatest minds in history — can certainly be labeled as a case of “AI psychosis”, but actually evokes a much more sinister framing under the context of referential mania: “through this tool, is my purpose to answer a certain unanswerable question?”

Crucially, this is why the search for proofs that have never been formalized, or for damning evidence of conspiracies that cannot possibly be proven, so reliably fry people’s brains. Politics is the number-one modern day example of incinerating your cognitive faculties, but there are still souls out there who think that GameStop is inevitably going to short squeeze the current financial system out of existence.

Yet, in some sense, this is harmless — the GameStop people are in much healthier mental places than the politics people. Why is this?

A core belief of mine is that humans are creatures of faith, and that there is no way to explicitly sort things by “verifiably true or false”, and that pursuing such a worldview is quite stunted. As Kriss puts it

I think the universe is not a collection of true facts; I think a good forty to fifty percent of it consists of lies, myths, ambiguities, ghosts, and chasms of meaning that are not ours to plumb. I think an accurate description of the universe will necessarily be shot through with lies, because everything that exists also partakes of unreality. And probably the best piece of evidence for my view is rationalism itself. Because in their attempts to clearly separate truth from error, they’ve ended up producing an ungodly colloid of the two that I could never even hope to imitate.

But that’s precisely where liquidity theory comes in: if something is speculated upon and transacts, it conveys information: it gives you an idea of which side people are on, how it’s changed over time, and most importantly, it provides some form of validation in the form of PnL.

Everything predictable can be framed as an option that becomes more and more predictable until it hits the moment of expiry. Anything else is unknowable. That’s the line…

Trying to explain the unprovable is precisely the reason why people get lost in fake models and prophets and signals that don’t really explain why anything trades and get depressed. Trading is the postmodern religion. It can’t be knowable, but it can make you money, because we bucket reality into time.

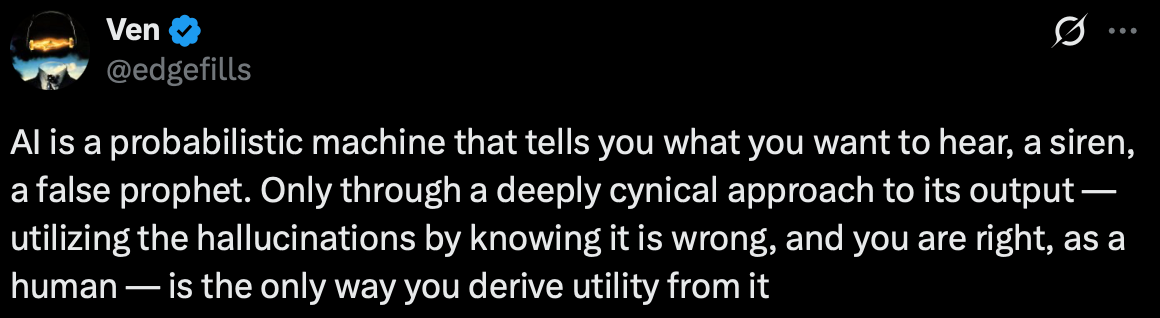

To insulate oneself from the siren song, one must not necessarily take a cynical approach to the output, but certainly an egoless one: “Can the conclusion I’m deriving be framed as an option that can properly be speculated on and resolved?”

(Note that prediction markets are a rudimentary, but proper framing of the idea that generating stakes through prop bets is the only way to gauge conviction — else people, convinced of their intelligence, will exclude real people from the conspiracy that they alone see.)

By blending profit and conviction, striking a balance between the desire to be correct and understanding that profit is imperfect confirmation of intuition, and that a true “reason” that you were correct cannot be known, you can tether yourself to a self-defined, accepted mode of reality.

Thus, the proper approach isn’t to “label” facts versus reality, or spend time developing the perfect “AI detection” tool. It really just comes down to being comfortable that certain things just can’t be known for certain, that it is a form of amusement to keep us plodding away.

In part 2 — unsure of whether this comes before or after the year-in-review post — I’ll delve into a more psychoanalytic approach to framing questions, and how to pull yourself out of a frenzied feedback loop.

Hey, if you like procedural TV shows? You might also get a kick out of Leverage and/or Psych. As well as Numb3rs and White Collar.

"Thus, the proper approach isn’t to “label” facts versus reality, or spend time developing the perfect “AI detection” tool. It really just comes down to being comfortable that certain things just can’t be known for certain, that it is a form of amusement to keep us plodding away."

Love this. Trying to pursue absolute truths is how you become cynical and depressed. You need to accept the known unknowns for what they are.