How I Short Stocks

I'm not a magician, I reveal my tricks

Stan Druckenmiller has a famous quote about shorting stocks:

I just try to look at the current situation and then I try to think of a situation 12 to 18 months from now based on my forecast.

If I believe the security prices are going to be less, then I short them.

Frankly, I‘m not sure I’ve ever made money, if I took back the last 40 years. I’m afraid to look. I’ve never had a down year, but I’m not sure I’ve made money in shorts.

I like it. It’s fun, but you can get your head handed to you. It’s a game that really only professionals should play. The odds are against you.

I’m not as modest — my shorts are winners, but they are much bumpier rides than my longs (natürlich — markets are designed to go up over time.) Over the years, I’ve built up an intuitive toolbox on how to short stocks; now that I’m “out” of the game, I might as well reveal some tricks.

Ven’s Axioms of Short Selling:

1. Valuation is not a short thesis

It should be much more obvious in our current, postmodern market state, but “valuation” is a terrible reason to short a stock. What I believe trips people up is that, for a short to be profitable, it does require a collective realization that the shares are overvalued. So what’s the disconnect?

Valuation, at its core, is a psychological phenomenon. My favorite example is wristwatches — you can buy the exact same Rolex Submariner that Sean Connery wore, but simply due to the fact that Bond, James Bond wore it, that watch becomes exponentially more valuable. Thus, we understand that valuation, in a sense, is in part a story — the droll Excel manuscript tells a tale of “future cash flows”, and merely manipulating the inputs does not a compelling tale make. When someone tells me a stock is overvalued, I think back to that Mad Men scene where Pete is convinced he has ultimate leverage over Don Draper; Mr. Campbell, who cares?

2. If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation

Trading is, at its core, an information game. If your idea is too esoteric or incomprehensible, even if it’s a magic bullet, nothing will happen. If it’s too obvious, everyone catches on too quick and there’s no opportunity to profit. To redirect the narrative, there has to be a catalyst that makes everyone pay attention and reconsider. (Which is why volatility spikes when prices drop — increased uncertainty is reflected by people demanding bid-side liquidity as opposed to ask.)

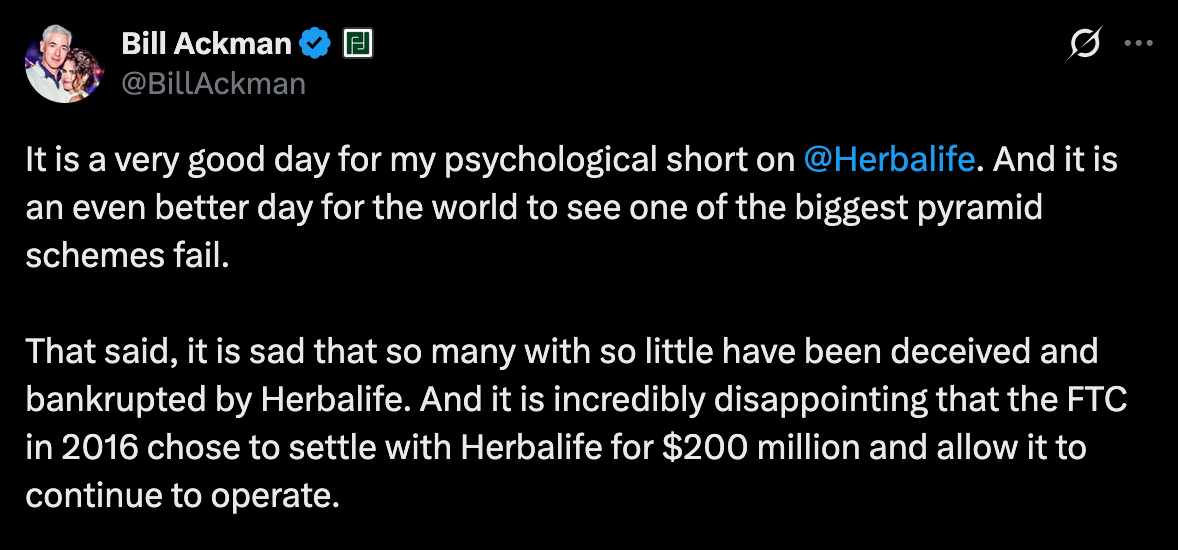

Constructing a short narrative is not going to make you a popular person — everyone wants their shares to go up without having to think about it. Bill Ackman exemplifies this perfectly — even though his trade didn’t work out monetarily, as opposed to psychologically (?),

everyone attaches the HLF-to-zero narrative to him, and plenty of people were rubbed the wrong way.

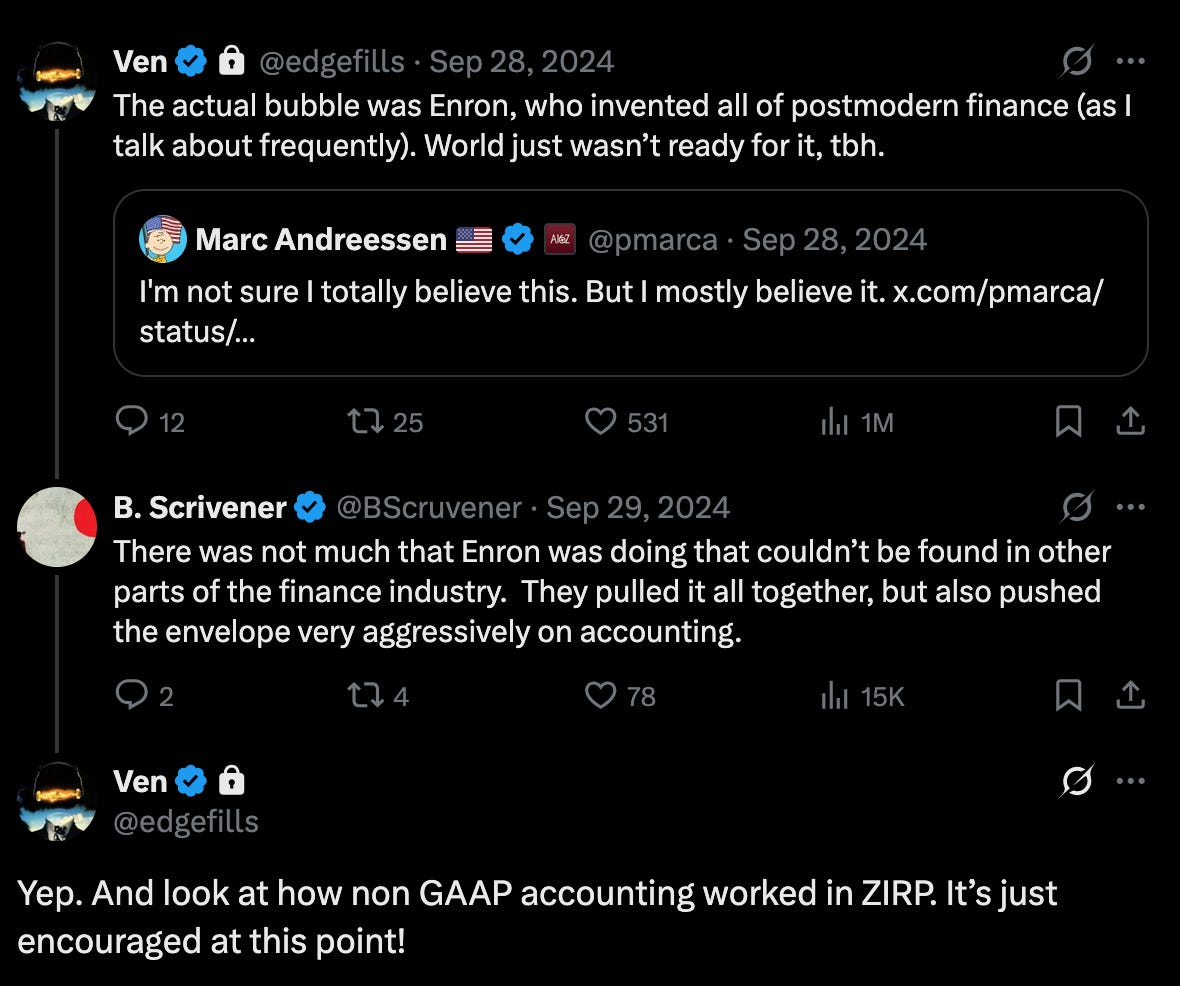

If you’re not trying to go on a crusade, the classic catalyst is quarterly earnings. In today’s day and age, where nearly everything Enron did is not only legal, but encouraged, numbers don’t really tell a coherent story.

Instead, we’re looking for the reframing of the narrative to come from inside the house itself, through guidance.

Here’s an example of an earnings short I took on DKNG back in February. While the beat framed the story initially, the narrative I was playing was: how does a market-maker of sports odds in an ultra tight competition for flow with an insanely high CAC relative to the net worths of its habitual players ever make money as more competitors (like prediction markets) enter the fray?

Trading the actual ER is a coin flip, trading a vibe shift requires patience. No matter what management says, everyone eventually goes back to their numbers. A short without a drawdown means you’re a genius, you’re insider trading, or it’s too obvious, and you should keep your eye on the exits and remain skittish.

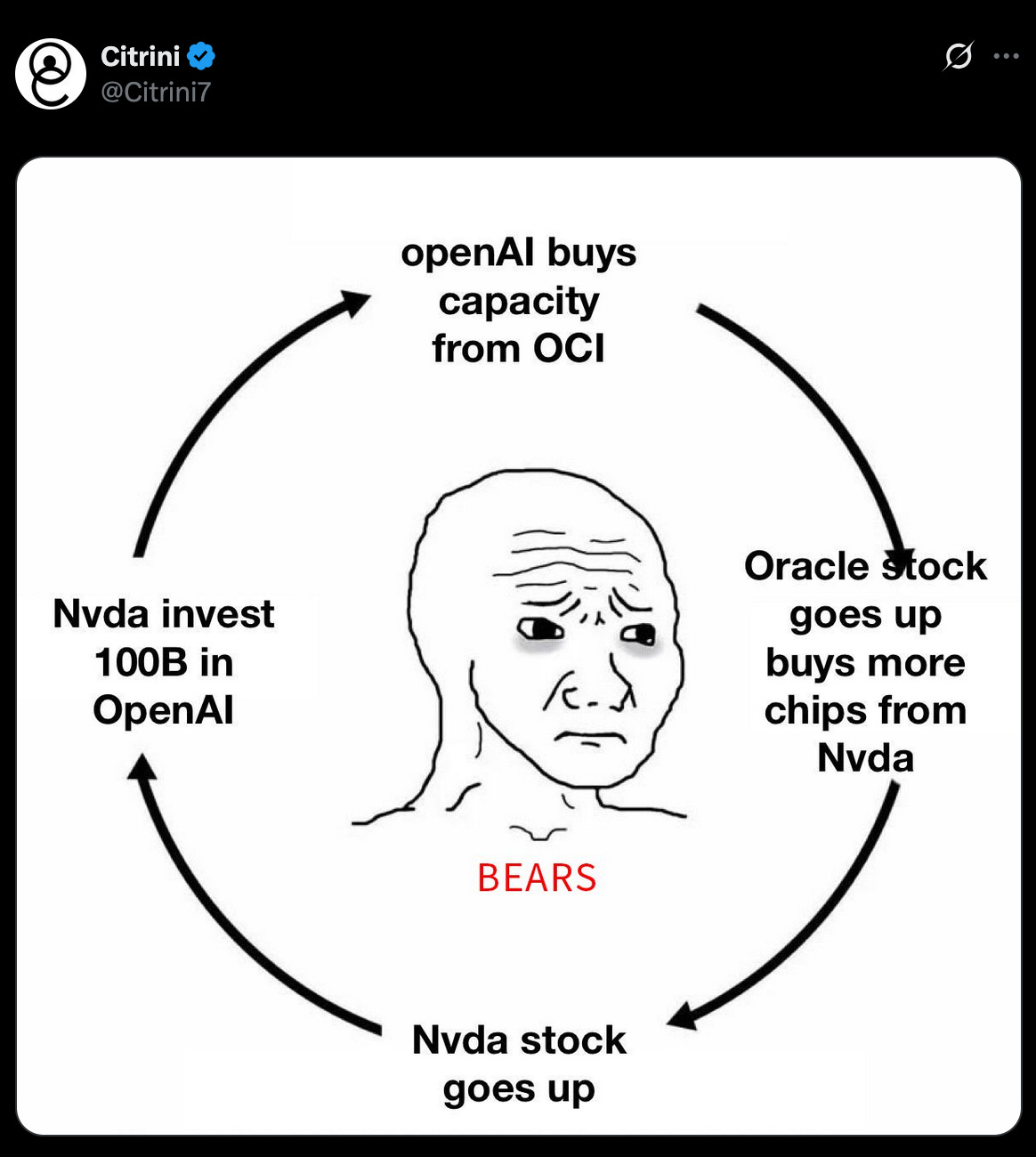

Another type of short I trade is a bit of a delightful psychological phenomenon — I like to take shorts at awe-inspiring market caps.

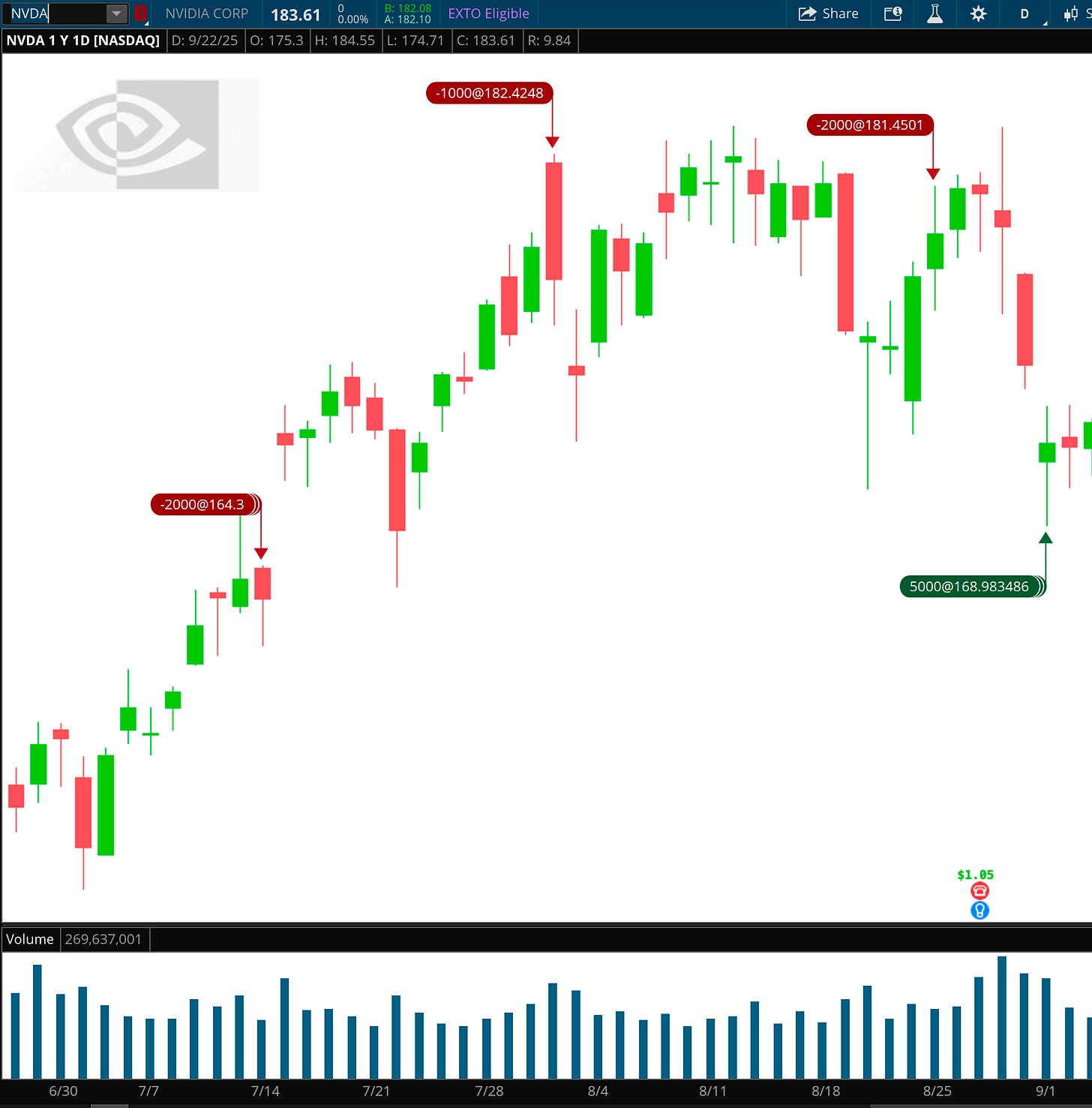

My absolute favorite headline to see when I’m looking for short exposure is a news blast about a new trillion-dollar market cap threshold being crossed. No matter what, in the back of everyone’s head, they think, “what exactly is a trillion dollars?” And while this trade can certainly melt up against you, as it did from 4 trillion onwards in the chart above, that’s a sign that the book has thinned out, and what goes up must come down. And, of course, excess demand for bid-side liquidity lends itself to much more rapid moves downward.

3. The “Big Short” misses the big picture

In both the previous examples, I was perfectly happy to be wrong. I only short when I need to reduce market exposure and can’t flatten, not because I want to get rich off something going to zero.

Think back to Ackman — shorting is a bit of an antisocial endeavor, the don’t pass line in craps; you win when everyone else loses. It’s necessary for a functioning market that shorts are rewarded when correct, but a very profitable short requires the monetization of a mass black-pilling vibe shift. “Don’t dance”, as Brad Pitt exclaimed in the movie, and I keep this in mind when betting on the downside.

Lost in yet another fantasy Michael Lewis narrative is that Burry’s investors were 100% in the right to be so mad at him. He was married to an idea that many smart people saw, but realized was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Winning on the bet where everyone loses their shirt leaves a bitter taste in everyone’s mouth, which inevitably leads to resentment — you’ve won, but at what cost?

I’d be fine if, say, the AI-bubble lasted forever. Bubbles are fun! Nobody actually wants a hot roll at the craps table to end, statistics be damned. Accordingly, I don’t tie my identity to “I told you so” in the event that everyone gets burned. You don’t want your big winner to be everyone else’s loss, karmically speaking. Always remember what it means to profit off the downside.

4. Undefined timelines are worth far more than defined risk

If you look at those charts again, you’ll see that I never buy puts when shorting. While puts cap your losses at the premium paid, it also caps your trade to a certain time horizon. It also traps you in a nonlinear timeline — if you buy longer dated puts and the stock goes down rapidly in a couple days, your position isn’t delta-sensitive enough to meaningfully profit. Conversely, short-dated puts are like spinning a triple-zero roulette wheel — narratives take time to disseminate and markets are biased upwards. Even if you profit, you’re just torturing yourself.

I prefer shorting shares. The beauty of the post-GME world is that I largely don’t pay interest to borrow shares anymore. The risk isn’t really “undefined” — when shorting a comprehensible market cap, I come up with a theoretical max buyout price. For example, if I’m shorting DKNG, a ~20bb company at time of writing, I know nobody is going to randomly tender an offer, say, beyond 40bb. I account for this as my max drawdown and size accordingly, usually in up to 3 chunks. In the case of NVDA, on the other hand, I mean, think about how much inflow it took to push it to 4 trillion in the first place, and how much “fundamental value” types foam at the mouth over this. Is it really reasonable to expect this to rapidly 2x from here? (If you’re uncomfortable/unable to do this, of course, just buy tail OTM calls.)

The benefit of this approach is that I can enjoy my life. If the catalyst doesn’t come, or the narrative doesn’t shift in my direction, no matter, I can flatten. Shorting profitably is a bonus, not a goal in and of itself — I’m actually shorting the vol of my own portfolio, reducing my leverage through negative delta one exposure. This is why math tells you to have L/S exposure at times, and why Druck still shorts even if it’s not profitable — if you do it right, your longs become even more profitable over time.

I hope this perspective helps — I don’t think anything I wrote was complex, but the mental framing really, really helps adjust from taking leverage through buying puts to gain downside exposure as opposed to reducing leverage through shorting stock to add downside exposure.